The climate that affects farming and the farming that saves the climate

The climate that affects farming and the farming that saves the climate

What do the countryside and the city have in common? Neither will survive the effects of climate change unscathed, and both need to rethink the impacts they cause on the environment. It was with this provocation that iCS established a partnership with the National Confederation of Rural Workers and Family Farmers (Contag), which brings together more than 4,000 unions in all the federative units and works to guarantee and expand the rights of 15 million rural workers.

Among the configurations of agricultural and livestock production, family farming is the most vulnerable to climate change. For this reason, in the last 12 years, terms such as agroecology, the responsible use of resources and sustainable agricultural practices to minimize negative environmental impacts and to improve the crop resilience, have become part of Contag meetings, with the creation of an Office for the Environment within the confederation. However, until then, the organization did not list these topics as being part of the global climate agenda. Recently, in 2022, the partnership with iCS intensified the discussions within the confederation and with its members.

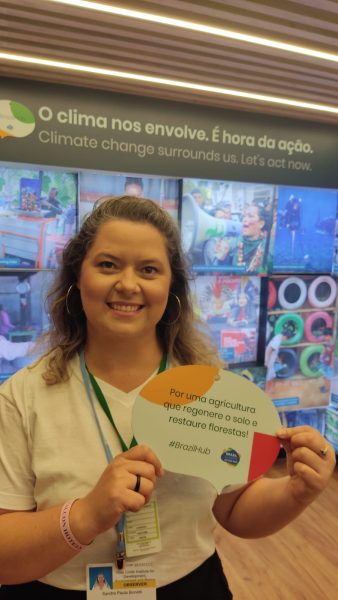

“When we talk of climate, we think about conferences and international negotiations and, at first, this appeared to be far from our reality. Little by little, iCS showed us that much of the political advocacy and our demands for healthy and sustainable production are in dialogue with the climate agenda,” says the Environmental Director of Contag, Sandra Paula Bonetti.

This is how, since the beginning of the partnership with iCS, Contag has promoted a series of online and in-person training about the climate agenda related to family farming, in order to train multipliers in all the states and the Federal District, published technical materials for the unions and held events of climate training and education. Ecosystem services, payments for environmental services, low carbon emission agriculture and environmental public policies are some examples of the topics that have been worked on.

Translating the climate agenda

According to the Statistical Yearbook of Family Farming, half of the Brazilians who live in rural areas have not completed elementary school. On average, they went to school for 7.2 years. For Bonetti, even though it is sometimes removed from academia, the countryside cannot be removed from the climate agenda, as it is part of the solution.

“The climate agenda seems designed so that the farmer does not understand it. It is extremely academic and literate, formulated by researchers who, for the most part, have never picked up a hoe and who have lived in an apartment for their entire lives. Therefore, the climate ends up being discussed from the perspective of cities and not the countryside. However, what if there is no food for the cities? We, the farmers, are as much impacted as the peripheries and the urban centers,” says Bonetti.

“We talk about the climate from our experience on the farm, based on what we see on a daily basis in the countryside. For example, in recent years, corn production has decreased, cassava cultivation has suffered strong impacts, and the South region has experienced three consecutive years of drought. The farmer knows this. It is not just a drought; it is a climate crisis. Our job is to establish this connection between the problems faced in the production and the climate, to show that this is a global issue that will affect their lives,” she adds.

From the farm to COP

With 20 years of experience in the trade union movement, Sandra relates the climate challenges to the lives of farmers with a knowledge of the facts. She grew up on a rural property in São Jorge d’Oeste, in Paraná, and is a popular educator, with a degree in Rural Education. Up to three years ago, she worked with her parents on the 7 hectares of their family farm. In 2022, she represented Contag at the United Nations Climate Conference (COP 27), in Egypt.

“Every day, when I go to a hearing, a meeting or an activity, I remember that my father wakes up every day at 05:00 to milk the cows and I have to do whatever it takes to improve his life and the lives of thousands who, just like him, need this representation. I am very convinced that this effort can save people, in the sense of their sovereignty, autonomy, food security, and retirement, by maintaining and appreciating their piece of land, their home,” she says.

In response to the decrease in the number of family farmers in the countryside (an 11% reduction in the last ten years, according to the yearbook), Bonetti wants the rural environment to be seen as a possible future. “I was a young activist. I am from a generation that had the option of leaving the countryside to go to other places, but remaining on the property is a choice. Currently, I am at Contag to improve people’s lives, in this transitional political space. I think about returning to my property, producing and staying there. My dream is that people see the countryside as a place of opportunities, of living well.”

Diversity in the countryside

Operational for over six decades, Contag is the first and largest farming union institution in the country. Since its creation in 1963, it has acted so that Brazilians from rural areas have decent living and working conditions ensured by differentiated policies, especially for family farming. These include social security, agricultural credit and insurance, land credit, technical assistance and rural extension, commercialization and the guarantee of minimum prices, cooperativism, associations and rural infrastructure, among others.

One of the maxims of the confederation is that Brazilian agriculture is multifaceted and, therefore, each region of the country faces different challenges. “In this immense scenario, family farming often ends up becoming invisible. It is difficult work, because the manpower involves family members and you have to self-manage, execute, and cover all the expenses. On a small property, the dynamics are very specific,” says Sandra Bonetti.

She argues, above all, that it is necessary to abandon the stereotypical view of the countryside. “Many people only see family farming as subsistence farming or as an outdated mode of production. And yet, it is multifaceted in its way of producing and bringing food to the table of the Brazilian worker.”

The diversity and productivity mentioned by Sandra are corroborated by the Statistical Yearbook of Family Farming. In its most recent edition, in 2023, it showed that Brazilian family farming is made up of women, men, and LGBTQIAP+ people, of all ethnicities and ages, including settlers, artisanal fishermen, quilombolas, indigenous peoples, foresters, aquaculturists and extractivists. The document also highlights that this segment is responsible for 67% of the occupations in the countryside and 23% of the gross value of the agricultural and livestock production in Brazil, which is the eighth largest food producer in the world.